Circuit Breakers (Stopping Cascading Failure Before It Spreads)

A first-principles explanation of circuit breakers, how cascading failures happen, and why stopping calls is sometimes safer than retrying.

When Failure Starts to Travel

A service slows down.

Clients retry.

Queues grow.

Threads block.

Soon, healthy services start failing too.

Nothing is “broken” —

but everything is overwhelmed.

This is cascading failure.

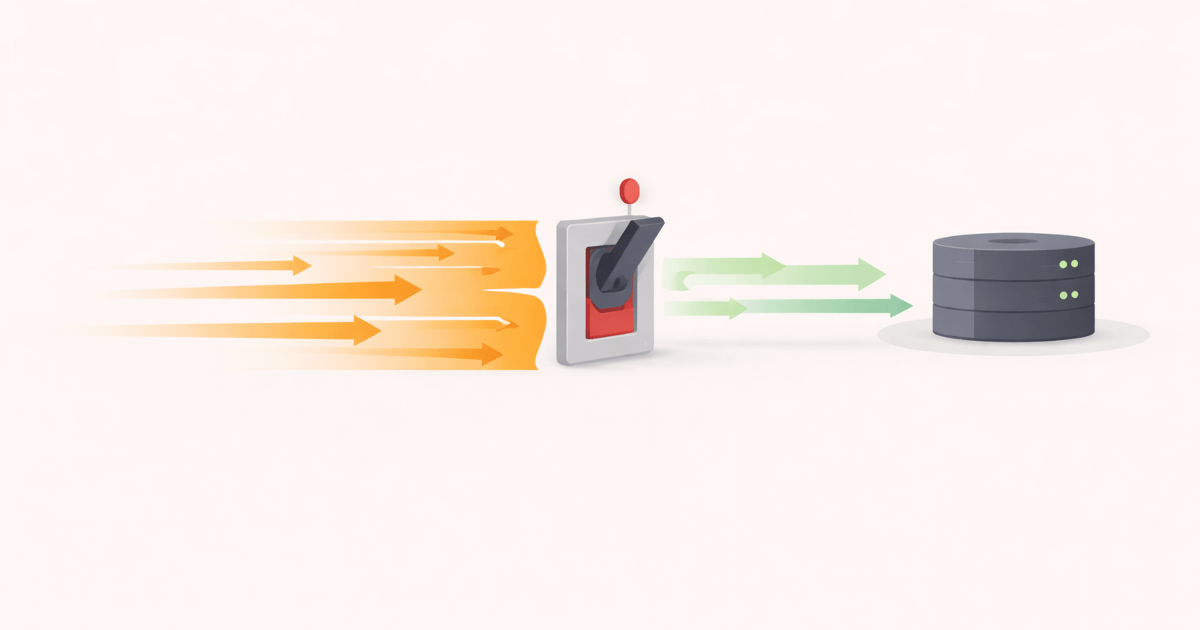

The Core Idea

A circuit breaker is a protective switch.

It answers one question:

Should we keep calling a service that is clearly unhealthy?

Sometimes the safest call

is not calling at all.

A Simple Analogy: Electrical Circuits

In your home:

- too much current → breaker trips

- power stops flowing

- damage is prevented

You don’t wait for wires to melt.

You cut the connection.

That’s exactly what circuit breakers do in software.

How Circuit Breakers Behave

A circuit breaker usually has three states:

- Closed — calls flow normally

- Open — calls are blocked immediately

- Half-open — a few test calls are allowed

The goal is simple:

- fail fast

- reduce pressure

- allow recovery

Visualizing a Circuit Breaker

stateDiagram-v2

Closed --> Open: failures exceed threshold

Open --> HalfOpen: after cooldown

HalfOpen --> Closed: success

HalfOpen --> Open: failure

This isn’t complexity.

It’s controlled hesitation.

Why Circuit Breakers Matter

Without circuit breakers:

- retries amplify failures

- slow services drag others down

- outages spread horizontally

With circuit breakers:

- failures are contained

- healthy systems stay responsive

- recovery becomes possible

⚠️ Common Trap

Trap: Relying only on retries.

Retries keep pressure on failing systems.

Circuit breakers remove pressure.

Both are needed — but for different reasons.

How This Connects to What We’ve Learned

Timeouts, Retries, and Backpressure

Decide when calls fail.

https://vivekmolkar.com/posts/timeouts-retries-backpressure/Sharding

Failures affect specific machines.

https://vivekmolkar.com/posts/sharding/Replication

Slow replicas can trigger breakers.

https://vivekmolkar.com/posts/replication/

Circuit breakers protect the system as a whole.

Retries try harder.

Circuit breakers know when to stop.

🧪 Mini Exercise

Think about a dependency you call often.

- What failure rate is acceptable?

- When should calls stop entirely?

- How does the system recover?

If you don’t answer these,

your outage will.

What Comes Next

Once failures are contained…

How do systems remain useful even when parts are down?

Next: Graceful Degradation

Designing useful failure instead of total collapse.